Introduction to rare metal germanium

Basic properties

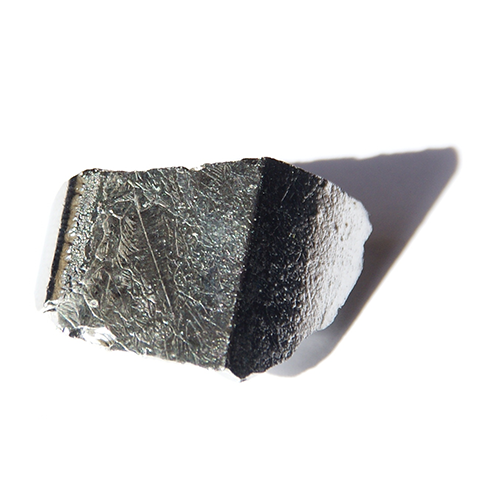

Germanium (Ge) is a metalloid element with atomic number 32, located in the 14th group (carbon group) of the fourth period of the periodic table, and has both metal and non-metal properties. Its crystal is a diamond cubic structure, brittle and hard, with a silvery-white metallic luster, a density of 5.323 g/cm³, and a melting point of 938.25°C. As an intrinsic semiconductor, its conductivity increases significantly with increasing temperature, laying the foundation for the early electronics industry.

Discovery history

In 1871, Mendeleev predicted the existence of germanium based on the periodic table and named it "silicon-like". In 1886, German chemist Clemens Winkler separated germanium from argyrodite and named it "Germania" in Latin, filling the gap in the periodic table.

Existence and extraction

The abundance of germanium in the earth's crust is only 1.5ppm. It is a dispersed element and is mainly associated with zinc ore, lignite and copper ore. In industry, germanium is recovered from the smoke and dust of zinc ore or coal fly ash, which is then distilled by chlorination to generate GeCl₄, then hydrolyzed and reduced to metallic germanium, and purified to ultra-high purity (99.9999999%) by regional smelting.

Physical and chemical properties

Germanium is stable to air and water at room temperature, oxidized to germanium dioxide (GeO₂) at high temperature, and soluble in concentrated acid and strong alkali to form corresponding salts. Its unique semiconductor properties and infrared light transparency (wavelength 2-15 μm) make it a core material for electronic and optical devices.

Application areas

Germanium is a key material for early transistors and is now used in high-frequency communication chips (SiGe alloys), space solar cells, and infrared optical systems (thermal imagers, missile guidance). Germanium dioxide (GeO₂) can improve the performance of optical fibers, and a small amount of germanium is added to the alloy to enhance strength and corrosion resistance.

Limitations and challenges

Germanium resources are scarce and the extraction cost is high, and it relies on associated minerals for recovery; some compounds (such as germane) are highly toxic and need to be strictly controlled. It is easy to oxidize at high temperatures, which limits its application in extreme environments, but its irreplaceable nature in high-end technology fields still drives demand.